Everybody thinks that classic films are individual,

one of a kind. That sort of makes sense, perhaps it is this individuality that makes

them classic. But some of the most beloved classic films had a past, they were

remakes of earlier films; the most notable being silents but some interesting

examples came from the most individual period in film history, Precode.

Although, some remakes have distinct and novel components that make them worthy

of study and praise, a lot have taken significant inspiration from their

predecessors and have altered some parts to remain relevant to the different

audience they are representing or attracting.

Even the most prestigious classic movie list – the

AFI’s 100 Years 100 Movies – is peppered by films that were first conceived in

the Precode or silent eras. The most popular is “The Wizard of Oz” (ranked 10

in the current list) which seems to be on a level of its own when considering

it’s individually and, certainly, its esteem in the minds of movie-goers.

However, few people know that the idea of “the wizard” was born in the mind

Frank Baum published as “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” in 1905 and even fewer

people know that that idea was first put onto film in 1925 starring the famous

– but not recognised today – Dorothy Dwan as Dorothy. Understandably, no one

can have the magic or singing ability that Judy Garland brought to the role and

when looking at both films they don’t have a lot, other than the basic plot

ideas, in common. But I cannot help but wonder whether Miss Garland and

the MGM produces didn’t take even a

little of the silent film as inspiration for what was to become a firm

favourite among contemporary and modern viewers.

Silent to Classic 1#: The Wizards of Oz

Although, interestingly at number 41, King

Kong (1933) has defied the issues of its age to become the only film in the

list to overshadow its more modern predecessor. This fact is puzzling; although

in my opinion the original is completely more entertaining than the 2005

version and, perhaps, its significance lies in the technological firsts that

stems from the films creation and not the storyline.

Precode to Classics 2#: The Scarfaces

Other, more interesting, Precode to classic remakes occurred during the

period of staunch regulation and the strictly followed code of behaviour in

between the years 1934 and 1966. Filmmakers could no longer explore the adult

ideas of sex, drugs, violence and relationships as blatantly as before and, it

seems, America vastly changed from the forward-thinking, economically-strapped

time of the early 30’s to thoughts of the ever present threat of war. Therefore,

remakes included extreme alterations: complete changes to the films endings,

the characters careers and behaviours and even general semantics – what worlds

could be used and in what context. Several movies suffered this fate. “The

Letter”, first a novel by Somerset Maugham, was dramatised in 1929 with the

famous but tragic Jeanne Eagels as its heroine. In this early talky Jeanne’s

character kills her lover when he threatens to leave her and, after a lengthy

trial, is acquitted thanks to the devotion of her husband. But this would not

do for the censors watching over the production of the 1940 Bette Davis film

of the same name, and the character is murdered in the final scene as a sort of

penance for her actions.

Precode to Classic 3#: The Letters

Another example is the fight over “The Maltese

Falcon”. The Precode version starring Richardo Cortez in the part Humphrey

Bogart made famous decades later was having a very obvious affair with his

secretary as well as the Brigid

O'Shaughnessy character – later played by Mary Astor. There are

unconcealed sexual scenes between the couples shown in silhouette or with

tricky camera angles as well as the amount of time Bebe Daniels spent lounging

in Ricardo’s apartment. But, as the code specified, scenes of that nature were

out with the nature of central relationship, in the classic 1941 remake, left

for audiences to assume and speculate. This situation is also shown in the film

couples: Rain (1932) and Miss Sadie Thompson (1953) and Cleopatra (1934) and

the Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor remake of (1963).

or:

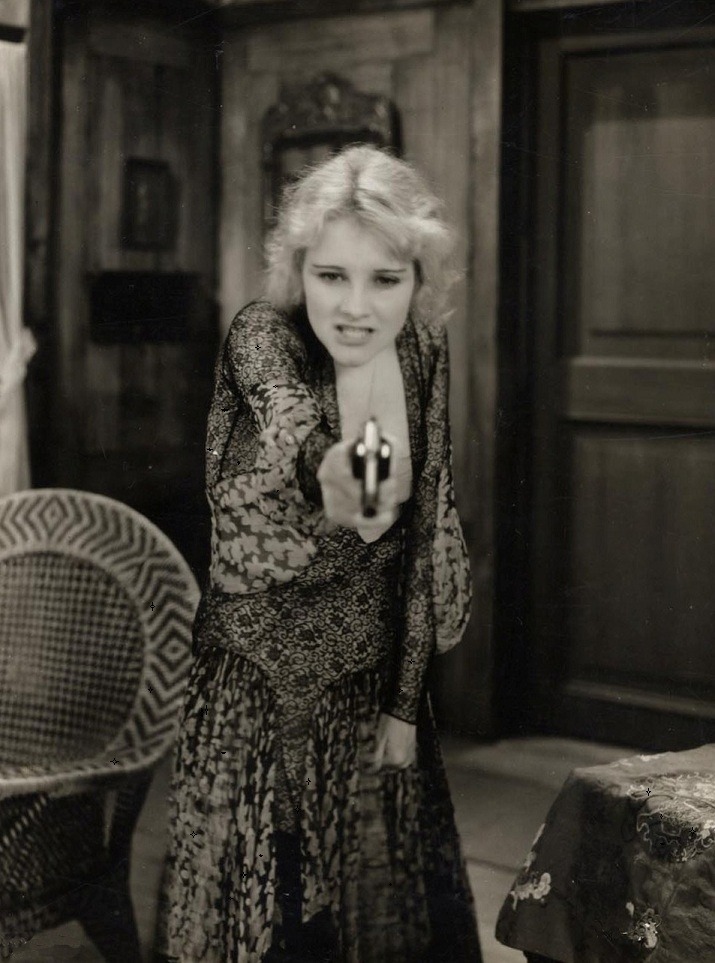

Alice White (with dark hair) and Ruth Taylor

Blink and you will miss it....

No comments:

Post a Comment