Brother Can You Spare a Dime - Movie Musicals and American Turmoil

Even Edison’s – a scientist not an artist – first

film was centred around music and its effect on his male friends. But then,

poor Edison only had the power to create moving images and the beauty of the

sound needed to be inferred rather than experienced. Decades later, brought the

change that audiences needed – talking picture. This new type of movie

experience meant a fan could hear as well as see their favourite star and the

age of the great scriptwriters was born.

The allure of the sparkling sequined costumes,

faced-paced dancing, gleaming smiles and dreamlike backdrops have fascinated

both the movies contemporary audiences and those of today. The actors and

actresses have profited from the new medium – Judy is instantly synonymous with

the bird-like singing and child-like innocence of Dorothy in ‘Wizard of Oz’ and

when the name Fred Astaire is mentioned people immediately think of his light

feat and the complicated choreography of ‘Top Hat’ or ‘Funny Face’.

While watching a couple of my favourite musicals I

noticed something extraordinary. Some, such as, the above mentioned ‘Funny

Face’ or even ‘The Wizard of Oz’ were created simply for entertainment but

others, some forgotten or some less commercial, speak to the audience on a

deeper level. They do this by commenting on the social situation of the period,

offering an escape or simply showing the living standards of the majority of

Americans to create a kind of solidarity. In this filmmakers were using not

only words and faces, but song and dance to communicate and persuade viewers to

see their viewpoint on certain social issues. And this seemed to work. By

removing the serious undertones of the problem, filmmakers were able to reach

more people than before, mainly when discussing the two most serious events in

American history – the Great Depression and World War II.

Exhibit 1# Busby Berkley. Here was a director that

not only had an opinion on the financial and political state of America in the

early 1930’s but vivid imagination and the ability to produce stunning yet

simple musical scenes. Also, it is interesting to note that his dance numbers

showed a need to rebel, such as his a subtle contempt of the institutions that

governed the making of his films, namely the Legion of Decency and the MPPDA.

His great accomplishment was the depression era film, ‘Gold-digger’s of 1933’

(1933) in which nearly all the dance scenes have some political remark either

explicit or implicit. Indeed, within the

first few minutes the viewer is bombarded by the beautiful Ginger Rogers and a

line of scantily clad chorus girls singing, “We’re in the Money” a song

glamorizing the ways of a ‘gold-digger’ and the poverty she faced after the

stock market crash. And, to leave audiences astounded, the final minutes are

filled by Joan Blondell singing (although I hear it was dubbed) the moving

“Forgotten Man” number amongst a backdrop of poverty riddled streets and

homeless men. The song comments on something slightly different from the problems

with the depression but the treatment of army veterans who, when they returned

from World War I, faced high unemployment and little welfare.

Although, these

are blatant stabs at the wellbeing of ordinary people, the light-hearted song

“Pettin’ in the Park” sung by Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell could also be

interpreted as, in some ways, politically motivated more by the use of its

chorography than its lyrics. It is well known that Busby hated the censors and

the Hays Code that was meant to reduce indecent and violent behaviour from

being shown. In this number, he deliberately goes against the organisation and

depicts images of nude women covered only by a transparent shade and uses

several unconcealed sexual

Although, these

are blatant stabs at the wellbeing of ordinary people, the light-hearted song

“Pettin’ in the Park” sung by Ruby Keeler and Dick Powell could also be

interpreted as, in some ways, politically motivated more by the use of its

chorography than its lyrics. It is well known that Busby hated the censors and

the Hays Code that was meant to reduce indecent and violent behaviour from

being shown. In this number, he deliberately goes against the organisation and

depicts images of nude women covered only by a transparent shade and uses

several unconcealed sexual

Busby was no one hit wonder. As a director, film

after film was filled with social comments, jabs at authority and jokes at the

failing censorship system. I will never forget the

strange image of Franklin D. Roosevelt flashed on the screen during the song

‘Shanghai Lil’ performed by James Cagney and Ruby Keeler in ‘Footlight Parade’

(1933). He was a pioneer but not the only director experimenting with the

musical form.

Busby's great politcal statement in 'Footlight Parade' (1933)

Fast-forward to the early 40’s and America is again

involved in a major world-wide event affecting more than just particular

factions of society but all Americans, World War II.

But this time, instead of rebelling against

authority like their depression-era comrades, these directors followed the

governments lead and used their power to promote nationalism and the importance

of the war to their audiences. Even dramatic stars wanted a piece of the

musical action heading variety-based films made solely to boost the morale of

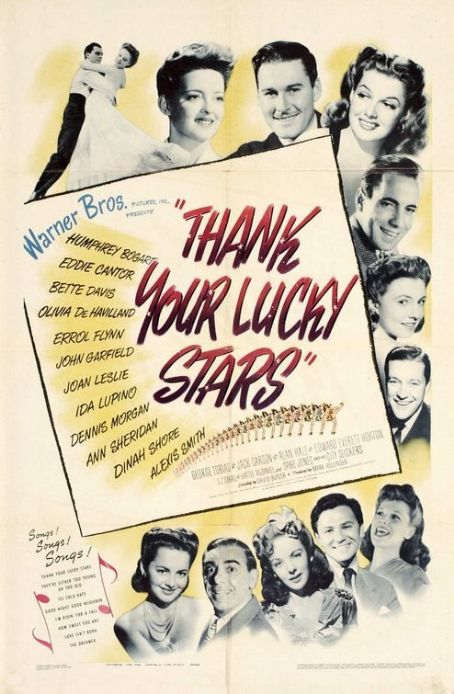

the anxious nation. Bette Davis and John Garfield, were the leaders of this

movement creating and starring in ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ (1943) where famous

actors and actresses would contribute short clips later transformed into a film

with most of the profits were donated to the cause. Most of the scenes were

musical with Bette and even the dapper Errol Flynn singing for the enjoyment of

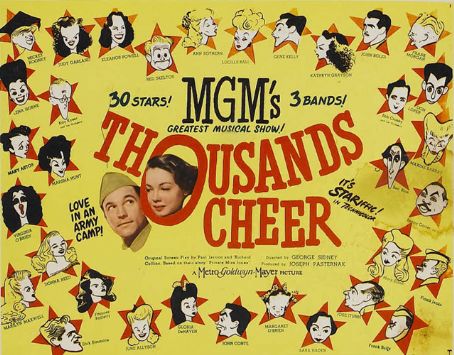

audiences. After the success of Warner’s film, other studios soon followed with

United Artists releasing its own edition, ‘Stage Door Canteen’ (1943) featuring

Katherine Hepburn and Tallulah Bankhead and MGM’s fluffy ‘Thousand’s Cheer’

also made in 1943.

Viewing

these films today they seem more propaganda than daring, political musicals.

They seem to skim over the harsh realities of the war and attempt to enhance

sentiments of nationalism and pride. But the musicals of the Precode and war

era’s have more in common than just political undertones, they both appear to

capture the emotions and needs of the country at those times. During the 30’s

the people were rebelling, they wanted change and a loosening in the social

strictures – that’s what Busby communicated. During the 40’s, Americans needed

hope, an escape and reassurance that the war was worth the sacrifice and the

musicals boosted and reinforced those desires. Musicals will always be relied upon enliven

the hearts of viewers. Their power lies not only with their beauty and joy but

the uncanny way of speaking on a deeper, more political level without audiences

even knowing it.

Footlight Parade's daring political statement, 'Forgotten Man'

Blink and you will miss it...

In the Depression the people needed to dream and the musical ones were helping to it

ReplyDeleteA good study that more of the seventh position was deserving

Wasn't "Remember My Forgotten Man" at the end of "Gold Diggers Of 1933," not "Footlight Parade"?

ReplyDeleteYou're right!! Its seems strange, because I watch Gold Diggers at least once a week. Its taught not to write late at night. Thanks, I am going to change it now.

ReplyDelete